the fallacy of the stolen concept: the act of using a concept while ignoring, contradicting or denying the validity of the concepts on which it logically and genetically depends.

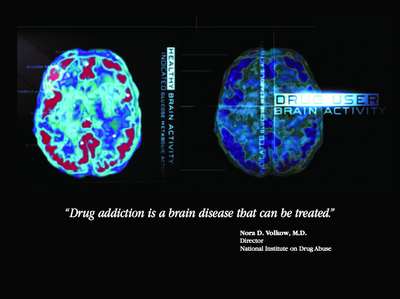

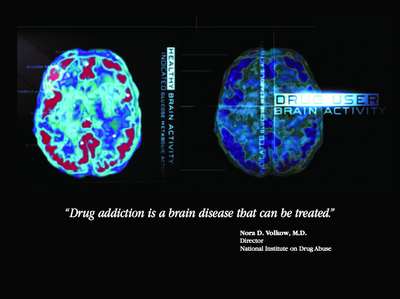

In the vision of addiction as a brain disease presented by today’s recovery propagandists, they present what they feel is a smoking gun – the brain scan. Basically, it’s a pretty picture of the brain of an active substance user, which they compare against the brain of someone who doesn’t use drugs. They’re quick to point out that there are readily visible differences – that the brain of the addict has been changed by their repeated choices to use drugs. Then, those of us who reject the disease concept are laughed at as fools who ignore the overwhelming evidence that addiction is indeed a brain disease. Of course, these “scientists” (and I use the term loosely, because they’re so incredibly dumb) are referring to a process of neuroplasticity when they make such an argument. Yet they go on to claim that the brain is so altered that only a medical intervention can hope to address it; that these brain changes will always be there and the subject will always crave drugs for the rest of their lives as a result – and that one can only hope to learn to cope with the effects; and that they need more money so they can design a medication to solve this problem.

In the vision of addiction as a brain disease presented by today’s recovery propagandists, they present what they feel is a smoking gun – the brain scan. Basically, it’s a pretty picture of the brain of an active substance user, which they compare against the brain of someone who doesn’t use drugs. They’re quick to point out that there are readily visible differences – that the brain of the addict has been changed by their repeated choices to use drugs. Then, those of us who reject the disease concept are laughed at as fools who ignore the overwhelming evidence that addiction is indeed a brain disease. Of course, these “scientists” (and I use the term loosely, because they’re so incredibly dumb) are referring to a process of neuroplasticity when they make such an argument. Yet they go on to claim that the brain is so altered that only a medical intervention can hope to address it; that these brain changes will always be there and the subject will always crave drugs for the rest of their lives as a result – and that one can only hope to learn to cope with the effects; and that they need more money so they can design a medication to solve this problem.

Neuroscience is a burgeoning field where innovation and new discoveries have been occurring at light speed over the last decade or two. What’s been found, contrary to earlier beliefs that the brain was hard-wired in the womb or childhood, is that the human brain retains neuroplasticity throughout our entire lives! That is, the brain is constantly changing throughout our lives. What’s more, advanced work by the likes of Jeffrey Schwartz has shown that it doesn’t take a chemical agent such as heroin or methamphetamine to effect neuroplastic changes in the brain – mere thoughts, attention, and the power of personal focus create changes in the brain. Such mental activity creates strengthened brain circuits and neuronal connections. The brain scans are compelling, and they have their place, but they must be accompanied by logic, that is, the facts need to be interpreted in a way that makes sense – or the results can be dangerous. For example, an idiot may see such results and proclaim that addiction is a brain disease, thereby misleading people into believing that they can’t change their behavior without a medical miracle which still doesn’t exist!

To understand neuroplasticity, it may help to look at the brain like a muscle of sorts. When you make it a habit to work, say your abdominal muscles, very hard every day at the gym, you will end up with six-pack abs. At first the workouts take a lot of effort, yet over time as the muscles increase in strength and size, the workouts become easier, and they feel more automatic. The six-pack is kept in shape almost mindlessly at this point, or at least without the same level of work with which you originally created it. But when you stop working those muscles altogether, they go away. You may work other muscles in the meantime and increase those, but the lack of working the abs destroys the six pack – and it will include much effort and focus to regain the six-pack. In the same way that the muscles we focus on in a work out will increase in size and strength, and the ones we ignore may decrease – the brain areas that we focus on and exercise will increase in strength and size, and the ones we ignore or deprive of activity will decrease. The brain, is like a bunch of muscles. This is why people don’t become “instantly addicted” when they do drugs – and indeed, this logic is built into the brain disease model of addiction – to a degree.

In the brain disease model, it goes that there isn’t really a pre-existing condition, but that the brain circuits which respond to drug use become increasingly larger or strengthened as someone repeatedly uses drugs in an intense fashion – so here the argument is built upon neuroplasticity. The anti-brain-disease argument doesn’t deny this – it simply asks for consistency. Where the brain-disease theorists engage in conceptual theft is when they build their case upon the principles of neuroplasticity while simultaneously denying the principles of neuroplasticity. Again:

the fallacy of the stolen concept: the act of using a concept while ignoring, contradicting or denying the validity of the concepts on which it logically and genetically depends.

The part of the brain-disease argument which denies neuroplasticity is when they claim that substance users cross a threshold whereby their brain will remain forever changed, and only medicine can effect a change. The brain circuits were strengthened through repetition and focus, and if the user simply finds something else to focus on, they will in turn ignore the muscle in question, depriving it of any exercise, and allow it to shrink, while they work another brain muscle. This is how people change their habits every day. My grandmother did it quite simply when she decided to chew gum or work on some gardening whenever she felt like smoking a cigarette. She broke a 40 year smoking habit that way. Scientists who care about solving a problem rather than finding new ways to try to support the addiction-as-disease political agenda, are doing research which logically confirms the process that my grandmother and so many others have used to change their habits, and they’re being intellectually honest about the results (see Jeffrey Schwartz).

Perhaps I’m wrong, but if so, then we should consider six-pack abs a symptom of a disease called ab-ism.

Note: There are plenty of other problems with the brain disease model of addiction, perhaps most notably that an actual loss-of-control or “hijacking of free-will” is never proven in any way, only anecdotal evidence in the form of subjective reports of powerlessness from people who’ve been taught that they’re powerless by the recovery culture is ever offered up as evidence of compulsion i.e. involuntary behavior. I have covered these ideas elsewhere, but today, I just want to focus on the stolen concept fallacy. Essentially, I’m only noting this as a disclaimer here so that no one gets the erroneous idea that my acknowledgment of the validity of one part of the brain disease argument amounts to endorsement of the idea that such strengthened brain circuits lead to uncontrolled use, they don’t. Such brain changes only allow for automation, like any habit, such as brushing one’s teeth – if you were used to doing it every day, you might go about it automatically at some point, but that doesn’t mean it’s involuntary. If you had some reason to not brush your teeth, such as a recent oral surgery, you would then pay mind to the habit and keep yourself from engaging in it. That is, you were never out of control, you put yourself on auto-pilot in a way, because the activity aligned with your wants, and as soon as another want (for your oral stitches to heal) entered your consciousness, you took yourself off of auto-pilot. Make sense? Wow, now I’m really writing too much.

Addiction as a brain disease fits so neatly into the treatment agenda. Short-sighted (and yes, dumb) researchers are so enamored of these brain scans to bolster their position that they failed to follow their findings to a natural and logical conclusion — brains continuously change based on behaviors. Substance users and their families accept the disease idea because if offers a neat and tidy explanation of why they keep using and why they feel powerless to stop; unfortunately it offers absolutely no solution. It’s actually quite disturbing to see how giddy addiction researchers and the treatment community are over these findings; do you think those who discovered cancer or HIV were so giddy? It begs the question, why are they happy about learning that people are doomed to a lifetime of struggle, relapse and failure? Why are they so focused on proving that people can’t change instead of finding ways that people can? Because their primary goal is to prove their theory in spite of all evidence to the contrary — not to help people. That’s when people cross the line from researcher to propagandist. Give me enough money and I can prove “scientifically” anything you want me to prove!

I have a limited understanding of neuroplasticity. I do believe that the brain is capable of changing and does change throughout our entire life. What I am curious about is things that people learn. For example, riding a bicycle. Once the behaviours of riding a bicycle are learned, they are never forgotten no matter how long the length of time between riding. Does this type of neuroplasticity represent a permanent change in the brain that cannot be undone? Meaning, can a person by using thought and focus unlearn or reorganise brain structures in order to forget how to ride a bike? I am by no means implying that the process of neuroplasticity that occurs from habitually using drugs is the same as the processes used for learning how to ride a bicycle. As a student of psychology entering into the alcohol and drug field, I am curious about the differences between them. More specifically, I am asking could a part of the brain permanently change after repeated drug use that makes a person more acceptable to the behaviours associated with drug addiction?

There are many schools of thought as to whether or not addiction and alcoholism are a brain disease. It is true that the repetition of drinking and using will create stronger patterns but at what point does the uses reach a point of no return? The brain is certainly capable of making drastic change!