A reader recently suggested that in my presentation of addiction as a chosen behavior rather than a compulsive (i.e. unchosen) disease-caused behavior, that I am using a false dichotomy. He failed to present a third option, which is egregious enough when making such a charge, but then went on with the same old garbage argumentation that every disease-monger uses. He proceeded to quote some recent neuroscience findings as if they were some sort of smoking gun against my position that addiction is a chosen behavior pattern:

“Policy debates have often centered on whether addictive behaviour is a choice or a brain disease. This research allows us to view addiction as a pathology of choice. Dysfunction in brain regions that assign value to possible options may lead to choosing harmful behaviours.”

Read more at: http://medicalxpress.com/news/2013-05-addiction-disorder-decision-making.html#jCp

I have not read the whole paper. If the authors want to send it to me for free, then I’ll be glad to do so, but I’m not going to shell out 30 bucks to read more of the same trash that still fails to adequately address the one thing that every one of these studies fails to establish: the direction of causation.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s not that these studies are totally worthless. They do establish something: correlation. But correlation, my dear haters, is not causation. It isn’t. Figure out the difference, and then get back to me. Try starting with this wikipedia page: Correlation does not imply causation.

So here’s what the press release mentioned above contends: The authors say (rightly) that “addicted individuals place greater value on immediate rewards… over delayed rewards.” So far, I’m with them. But then, they go on to say that:

this perceived value of the drug at a given time can be visualized in the brains of addicted individuals by functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), and that imaging results can be used to predict subsequent consumption.

And again, I’m still with them. They’re looking at a part of the brain that they believe to be involved in the process of valuing, and they’re seeing a specific type of activity. They’re identifying a correlation between brain activity and subsequent behavior, and I do not deny this correlation. However, let’s be clear, it’s still just a correlation. It may represent some sort of causation. For example, I might conclude that “when a person highly values something, they then do (or consume, or etc) that thing that they value.” Or: “when a person values drug use, the part of their brain involved in valuing is active, and then they proceed to use drugs.” This however, is only an explanation of what is happening inside the brain while someone is contemplating and then using drugs. Causation isn’t really established by this correlation. What caused the value center to activate around drugs? Was it a belief system that drugs offer a beneficial experience? Or did this brain region just inexplicably assign value to drugs on it’s own? At one time or another, the activity gets stronger. Why is that? Was the person reviewing many things they might do for pleasure, and then settle upon something they’ve know to provide pleasure many times before, and think about it more, and how good it would be? Or did this brain region just jump into action on its own? These questions are never answered in such studies.

I don’t know the full lengths these researchers went to in this study (and I doubt my righteous commenter does either), so I’m going out on a limb here. But I’ve reached a tipping point with this research where I’m not going to assume they have anything new to offer unless they tell me they really do. If they established causation, they should put it in the press release and abstract. So, I’m gonna assume until I’ve been presented otherwise that they’ve done the same old thing here. They probably put smokers (people who already value cigarettes, as evidenced by their continuous smoking) into an FMRI machine, showed them pictures of cigarettes, and looked at which part of the brain gets activated when they view cigarettes. This process doesn’t establish causation, remember it only establishes correlation. But then as far as I can tell, their next step was to send some sort of shockwave through this brain region:

Dr. Dagher showed that a specific brain region called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (abbreviated DLPFC) regulates cigarette craving in response to drug cues – seeing people smoke, or smelling cigarettes – and that these induced cravings could be altered by inactivating the DLPFC by Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

And then after the shock, this part of the brain became less activated, and they stopped craving cigarettes so much. Again, this next step still doesn’t establish causation. It establishes the fact that if you screw around with the apparatus used to value and thus crave cigarettes, then you might handicap that process. It doesn’t tell us what sets that process in motion.

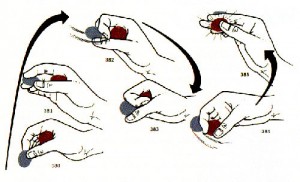

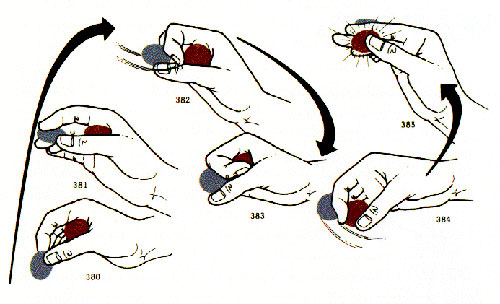

As an analogy, suppose I observed magicians, and measured their muscle movements while doing coin tricks. I find that a specific set of muscles surrounding the palm are integral to pulling off their tricks. Now, I see what happens when I inject those muscles with loads Novocaine to numb them up. PRESTO, they can’t do their fancy coin tricks until the numbness wears off. Does this ability to use a medical procedure to inhibit their ability to do a trick prove anything about why magicians do tricks in the first place? No, it doesn’t, and neither does shoving some magnetic energy into the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex prove anything about why people choose to smoke cigarettes.

As an analogy, suppose I observed magicians, and measured their muscle movements while doing coin tricks. I find that a specific set of muscles surrounding the palm are integral to pulling off their tricks. Now, I see what happens when I inject those muscles with loads Novocaine to numb them up. PRESTO, they can’t do their fancy coin tricks until the numbness wears off. Does this ability to use a medical procedure to inhibit their ability to do a trick prove anything about why magicians do tricks in the first place? No, it doesn’t, and neither does shoving some magnetic energy into the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex prove anything about why people choose to smoke cigarettes.

I have been reading the articles on your site for about 6 weeks. In 12-step culture, and I have been there and done it for years, it is common to hear that we can’t do the same behavior over and over and then expect different results. This isn’t literally true, of course, or who would practice free throws? But after 7 years of 12-stepping, it’s time to try something new. This is very stressful, because I basically have to rip out my foundation and I don’t have a replacement yet.

I accept that what I have been doing is voluntary. But I’ve come to a difficult puzzle. Once I accept that I’m behaving with choice, why would I continue on a path that is detrimental? I have also become more social over this same period of time, and so the consequences have become different. I identified a preference to be social, but (shocking) I’m mean and nasty when I drink a lot. I think the preference to be social is going to win, but I still have a sense of loss about what seems likely to change. I think I will miss drinking.